Key Takeaways

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a mental health condition involving intrusive thoughts (obsessions) and repetitive behaviors or mental actions (compulsions).

- OCD is not about neatness, perfectionism, or personality quirks.

- Intrusive thoughts feel unwanted, disturbing, and out of character (ego-dystonic).

- Compulsions provide temporary relief but make OCD stronger in the long run.

- OCD affects about 1 in 40 adults and can begin at any age.

- OCD is highly treatable with evidence-based therapies like ERP, CBT, I-CBT, ACT, and sometimes medication.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes, not medical advice.

Imagine living with a mind that constantly asks, “What if…?” What if I left the stove on? What if this thought means something terrible about me? What if I can’t trust my feelings, memories, or intentions? For people with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), these questions feel urgent, sticky, and impossible to ignore.

OCD is a mental health condition that causes people to experience intrusive thoughts and compulsions that interfere with daily life. But OCD is also one of the most misunderstood conditions. Many people think it’s about being tidy, organized, or particular; that’s simply not true.

This guide offers a clear, compassionate explanation of what OCD really is, how it shows up, and what treatment and recovery can look like. Take your time, move at your own pace, and explore the sections that feel most helpful to you.

What Is OCD?

According to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a chronic condition in which a person experiences obsessions, compulsions, or both.

Obsessions are intrusive, unwanted thoughts, images, or urges that cause distress.

Compulsions are the physical or mental acts someone feels driven to perform in response to these obsessions.

People with OCD usually know their fears are exaggerated or irrational, yet the thoughts feel intensely real. This is part of what makes OCD so painful. It is not a personality trait and has nothing to do with being “quirky,” “tidy,” or “particular.”

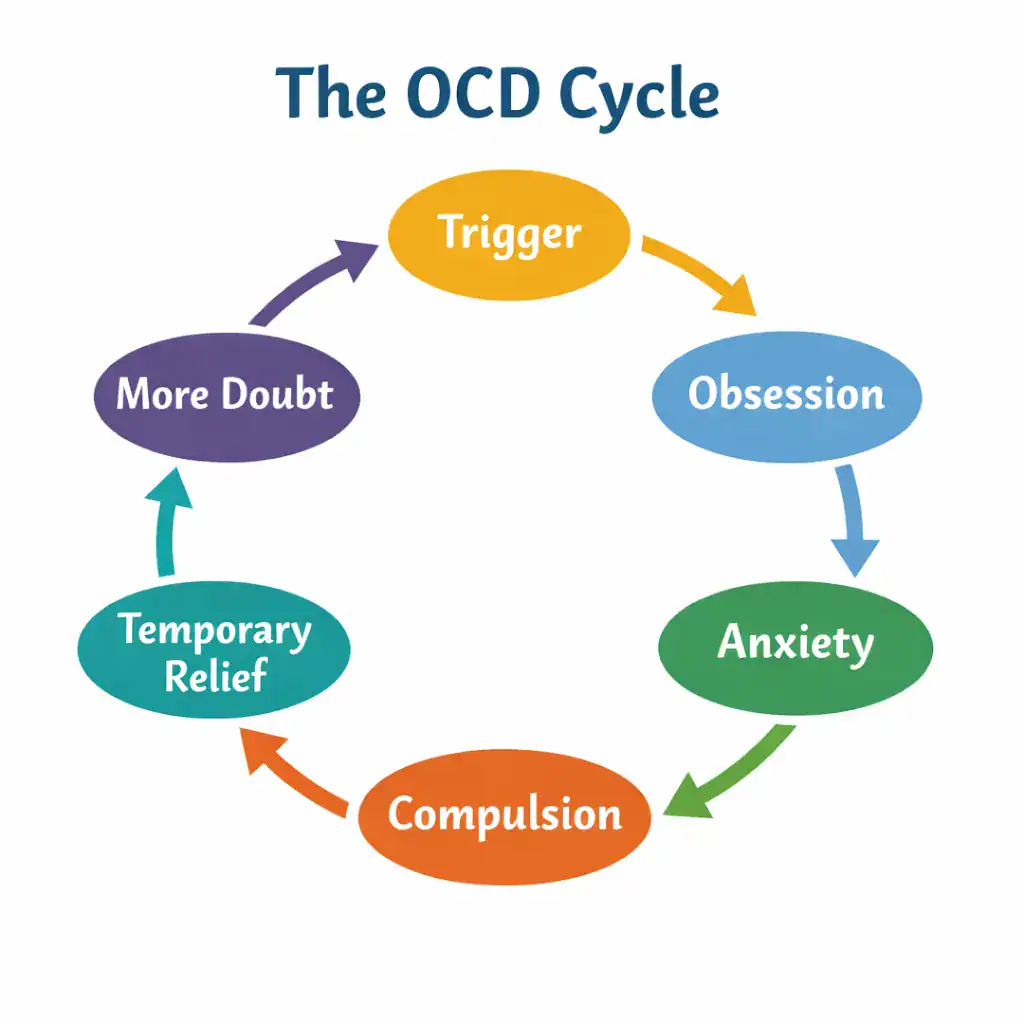

Individuals with OCD often find themselves caught in a frustrating cycle: an intrusive thought appears, anxiety rises, and a compulsion temporarily reduces the fear… until the next intrusive thought arrives.

OCD Key Facts

- About 1 in 40 adults currently live with OCD, according to a study in Molecular Psychiatry.

- OCD affects people of all genders, ages, backgrounds, and cultures.

- On average, it takes about 7 years for someone to receive an accurate diagnosis.

- OCD can begin in childhood, adolescence, or adulthood.

- OCD is not rare: it’s as common as diabetes.

- Many people with OCD experience high shame, which delays diagnosis and treatment.

- OCD is highly treatable, even when symptoms feel overwhelming.

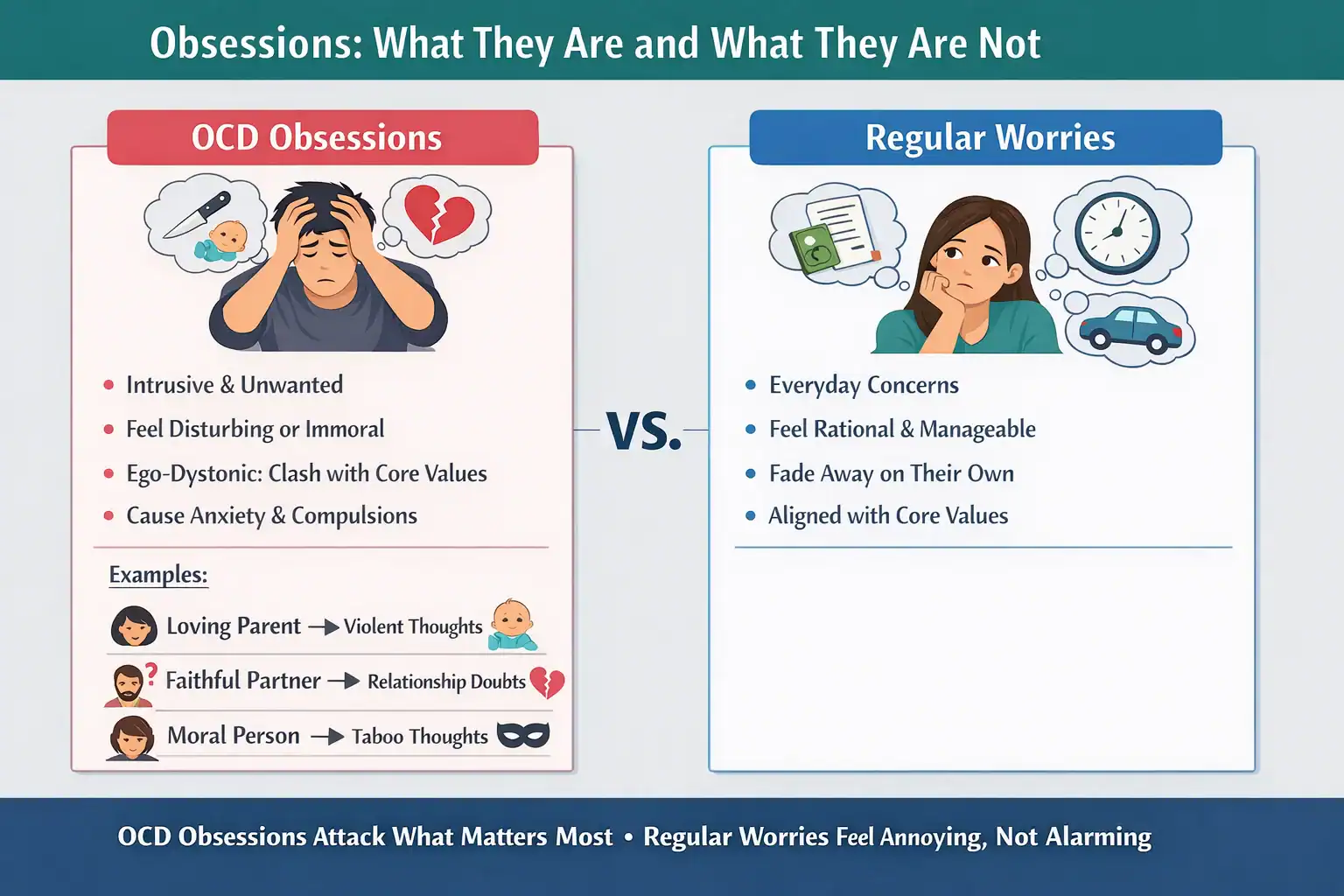

Obsessions: What They Are and What They Are Not

Obsessions are intrusive thoughts, images, or urges that:

- appear suddenly and without control.

- feel disturbing or unwanted.

- do not match the person’s values or character (ego-dystonic).

- create anxiety, doubt, or disgust.

Everyone has intrusive thoughts. However, in OCD, these thoughts stick, feel extremely meaningful, and trigger compulsions.

Importantly, OCD intrusive thoughts are ego-dystonic. This means that the thought goes against your identity. For example:

- A loving parent with a violent intrusive image.

- A faithful partner with intrusive doubts about their relationship.

- A moral, kind person having an intrusive, unwanted taboo thought.

In other words, OCD attacks what matters most. The more someone cares about a value, the more OCD targets it.

On the other hand, regular non-OCD repetitive thoughts don’t have the same “intrusive” quality as OCD obsessions. They may be annoying or stressful, but they usually:

- feel more connected to everyday concerns.

- don’t feel dangerous or immoral.

- fade on their own without compulsions.

- don’t clash with the person’s core values.

Regular worries might feel persistent, but they don’t create the same panic, urgency for certainty, or sense that the thought “says something about you” the way OCD obsessions do.

Common Types of Obsessions

- Contamination fears (germs, chemicals, illness).

- Harm fears (fear of hurting someone accidentally or intentionally).

- Sexual intrusive thoughts (taboo, disturbing themes).

- Relationship/ROCD (fears about compatibility, love, feelings).

- Religious/Moral scrupulosity (fear of sinning or being immoral).

- Existential fears (questions about reality, meaning, or identity).

Common Obsession Examples

- Doubting you locked the door or turned off appliances.

- Intense discomfort when objects aren’t arranged “correctly”.

- Worrying you might say or do something harmful.

- Intrusive memories or mental images.

- Fear of contamination from touching everyday objects.

What Are Compulsions?

Compulsions are behaviors or mental actions performed to:

- reduce anxiety.

- neutralize an intrusive thought.

- prevent a feared outcome.

- regain a sense of certainty or safety.

Compulsions can be visible (overt) or entirely in the mind (covert).

External (Overt) Compulsions

- Washing hands excessively.

- Repeatedly checking locks, appliances, or messages.

- Asking for reassurance (“Are you sure?”).

- Avoiding people, places, or objects.

Internal (Covert) Compulsions

- Rumination (“thinking your way” out of doubt).

- Mentally reviewing memories.

- Repeating phrases in your head.

- Trying to replace a “bad thought” with a “good thought”.

Common Compulsion Examples

- Washing hands until they’re raw.

- Checking doors or appliances repeatedly.

- Counting tiles, steps, or actions in specific patterns.

Why Compulsions Keep OCD Alive

Compulsions bring temporary relief, which teaches the brain: “This thought was dangerous. Good thing you neutralized it.” This reinforces the OCD cycle, making intrusive thoughts stronger, more frequent, and more convincing in the long run.

Learning to resist compulsions, achieved via Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP), is central to recovery.

The OCD Cycle

OCD follows a predictable loop:

Trigger → Obsession → Anxiety → Compulsion → Temporary Relief → More Doubt

Compulsions feel helpful in the moment, but they strengthen the entire cycle by signaling that the obsession was meaningful or dangerous.

Compulsions vs. Compulsive Traits and Rituals

Not all repetitive behaviors are unhealthy. People often use routines or rituals intentionally:

- a morning routine.

- arranging a desk neatly for focus.

- listening to the same playlist before studying.

These behaviors are chosen, enjoyable, or grounding.

A compulsion, on the other hand:

- is performed out of distress.

- feels mandatory.

- aims to prevent danger or avoid anxiety.

- becomes time-consuming or disruptive.

Can a Person with OCD Live a Normal Life?

Absolutely. With evidence-based treatment, many people with OCD can reduce the debilitating effects of the condition and become highly functional in all areas of their life, including school, work, dating, travel, parenting, and daily routines.

OCD is highly treatable, even after many years of going undiagnosed. Once people learn how to deal with their OCD, they regain a sense of confidence, freedom, and control.

Common Subtypes of OCD

OCD can manifest in many ways, but all subtypes share the same obsession-compulsion structure.

- Contamination OCD.

- Harm OCD.

- Relationship OCD (ROCD).

- Sexual Orientation OCD (SO-OCD).

- Pedophilia OCD (POCD).

- Religious Scrupulosity.

- Existential OCD.

- Health OCD.

- Magical Thinking OCD.

- Pure O.

- Postpartum OCD.

How OCD Shows Up: Real-Life Examples

These examples show how OCD adapts to different people, values, and situations but the cycle underneath remains the same.

Example 1: Worries About Harming Loved Ones

Lucas, age 16, is terrified by intrusive images of hurting people he loves. He avoids knives at home and repeatedly checks on his parents to make sure “everything is okay.”

He also ruminates constantly about these disturbing thoughts, wondering whether having them means he secretly wants to harm his parents or that he might be a psychopath. To counteract the fear, he mentally reviews a list of reasons he is a good, safe person. This compulsion consumes a significant amount of time each day.

Most poignantly, Lucas is horrified by these thoughts. His intense distress is actually a sign that the thoughts are ego-dystonic. They go against his values and identity, and are characteristic of Harm OCD, not intent to cause harm.

Example 2: A New Parent with Intrusive Thoughts

Marisol, a new mother, experiences sudden, vivid mental images of harming her baby. These thoughts are deeply distressing and cause intense anxiety, even though she has no urge or desire to harm her child.

She avoids carrying the baby alone and repeatedly reviews her actions to make sure she has not done anything wrong. She worries that having these thoughts means she is dangerous or unfit to be a mother.

Her fear becomes so overwhelming that she asks others to help care for her daughter because she is afraid to be alone with her. She has also begun taking an SSRI to reduce her anxiety and has started an outpatient treatment program.

Marisol is experiencing postpartum Harm OCD. Her intrusive thoughts are ego-dystonic and reflect her deep love, sense of responsibility, and fear of causing harm, not a desire to do so.

Example 3: College Student and Ritualistic Behavior

Carla, a college student, feels compelled to repeat a strict bedtime routine in a specific order before going to sleep. She believes that if she skips a step or does it “incorrectly,” something bad will happen, such as failing an exam. If she realizes she made a mistake, she feels an intense urge to start the entire routine over from the beginning.

This behavior began after the sudden death of her father, a period marked by grief, uncertainty, and a sense that life had become unpredictable. Over time, the ritual became a way to feel momentarily safe and in control. During high-stress periods, especially around exams, the routine grows longer and more rigid.

Although the rituals provide brief reassurance, they significantly disrupt her sleep and increase her overall stress. Carla often goes to bed late, exhausted, and anxious, which ironically makes it harder to focus academically, reinforcing her fears.

Carla knows the ritual is “weird” and doesn’t logically believe it causes exam outcomes, but the fear of not doing it feels unbearable. She feels deeply ashamed of this behavior and keeps it hidden from friends and family.

Example 4: Someone with Relationship OCD (ROCD)

Emily loves her partner and values the relationship deeply, yet she finds herself trapped in constant doubt about her feelings. Thoughts like “What if I don’t love him enough?” or “What if this doubt means the relationship is wrong?” appear suddenly and feel urgent and threatening. Instead of passing naturally, these thoughts stick and demand answers.

In response, Emily begins analyzing her emotions over and over. She scans her body for signs of love, compares her relationship to others, and replays conversations in her head looking for certainty. At times, she seeks reassurance from friends or searches online for signs that a relationship is “meant to be.”

Ironically, the more she tries to figure out how she really feels, the more distant and disconnected she feels from her partner. Moments that could be enjoyable become tests, and natural fluctuations in emotion are interpreted as proof that something is wrong. Although Emily knows that all relationships involve doubt at times, the fear feels impossible to ignore.

She feels ashamed of these thoughts and worries that having them says something bad about her character or her ability to love. Rather than helping her make a clear decision, the constant mental checking leaves her exhausted, anxious, and increasingly uncertain, a hallmark of Relationship OCD.

Example 5: Someone with Contamination OCD

Ryan experiences intense fear around contamination and illness. Everyday actions (such as shaking hands, touching door handles, or sitting in public spaces) trigger intrusive thoughts about germs and the possibility of getting sick or contaminating others. These thoughts feel immediate and difficult to dismiss, even when he knows the risk is low.

In response, Ryan begins to avoid social situations altogether or engages in subtle compulsions, such as sanitizing his hands repeatedly or carefully monitoring what he touches. Social events that once felt casual now feel mentally exhausting, as he is constantly scanning his environment for potential threats.

Although these behaviors provide short-term relief, they gradually shrink his world. He turns down invitations, feels disconnected from friends, and grows frustrated with himself for not being able to “just relax.” He recognizes that his fear is excessive, but the discomfort of not responding to it feels unbearable.

What OCD Is Not

Because OCD is widely misunderstood, it’s important to clarify what doesn’t qualify as OCD.

- OCD is not perfectionism: Being detail-oriented, wanting things “just right,” or enjoying organization does not mean someone has OCD.

- Liking things neat is not the same as OCD: Many people prefer clean or aesthetically pleasing spaces. That preference does not involve intrusive thoughts or compulsions.

- Anxiety alone doesn’t equate to OCD: OCD is not simply “being anxious.” It is a cycle driven by intrusive thoughts, meaning attached to those thoughts, and compulsive responses.

OCD vs. Regular Thoughts

People often ask: “How do I know whether this is OCD or just normal worry or overthinking?” OCD-style rumination works differently from regular overthinking. It is repetitive and compulsive, driven by an urgent need to achieve certainty or prevent danger.

In OCD, thinking doesn’t feel optional or curiosity-based; it feels necessary. Rather than leading to clarity or resolution, rumination increases anxiety and keeps the mind stuck in loops of doubt. Even when the person recognizes that the thinking isn’t helpful or logical, it can feel extremely difficult to stop, reinforcing the cycle of OCD.

| OCD | Everyday Thoughts |

|---|---|

|

|

How OCD Differs from Other Conditions

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

In Generalized Anxiety Disorder, worry tends to be broad, ongoing, and focused on everyday life concerns such as work, health, or relationships. The worries feel excessive but usually relate to real-life situations. Unlike OCD, these thoughts are not typically intrusive, ego-dystonic, or tied to compulsive behaviors.

OCPD (Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder)

Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder is a personality pattern characterized by rigidity, perfectionism, and a strong need for control. These traits are often experienced as appropriate or justified by the person. Unlike OCD, OCPD does not involve intrusive thoughts or compulsions performed to reduce anxiety.

Trauma Response

Trauma-related intrusive thoughts are connected to real past events and often involve memories, sensations, or images related to the trauma. These thoughts arise from the nervous system’s attempt to protect against future danger. In OCD, intrusive thoughts are not tied to actual events and feel irrational or alien.

Depression Rumination

Depressive rumination typically involves repeated thinking about past mistakes, personal failures, or feelings of hopelessness. The focus is often inward and self-critical rather than fear-based. Unlike OCD, this rumination is not driven by intrusive threats or an urgent need to prevent harm or uncertainty.

Causes of OCD

There is no single cause of OCD. Instead, research suggests that several factors contribute:

- Genetics: OCD tends to run in families, suggesting a hereditary component.

- Brain circuitry: Brain imaging studies show differences in the areas involved in fear, decision-making, and error detection.

- Temperament: People with high anxiety sensitivity or a strong sense of responsibility may be more prone to OCD.

- Stress and major life events: Transitions, loss, new responsibilities, or trauma can trigger or worsen symptoms.

- Reinforcement through compulsions: Every time a compulsion temporarily reduces fear, it reinforces the belief that the obsession was dangerous, strengthening the cycle.

How OCD Is Diagnosed

A formal diagnosis is typically made by a licensed mental-health professional using the DSM-5 criteria.

During a clinical interview, the therapist will ask about:

- intrusive thoughts

- compulsions (including mental ones)

- avoidance behaviors

- how symptoms interfere with daily life

To diagnose OCD, clinicians look for a clear pattern of the OCD cycle at work: obsession, anxiety, and compulsion. They assess the level of distress and impairment caused by these symptoms, the amount of time spent on compulsions, and repeated attempts to gain certainty or prevent feared outcomes.

Self-Diagnosis vs. Professional Assessment

Many people first recognize OCD through online resources, articles, or relatable personal stories. Self-diagnosis can be an important first step toward understanding what’s happening and seeking support.

However, a professional assessment helps confirm the diagnosis, rule out related conditions, and guide treatment toward evidence-based approaches tailored to the individual’s specific symptoms and needs.

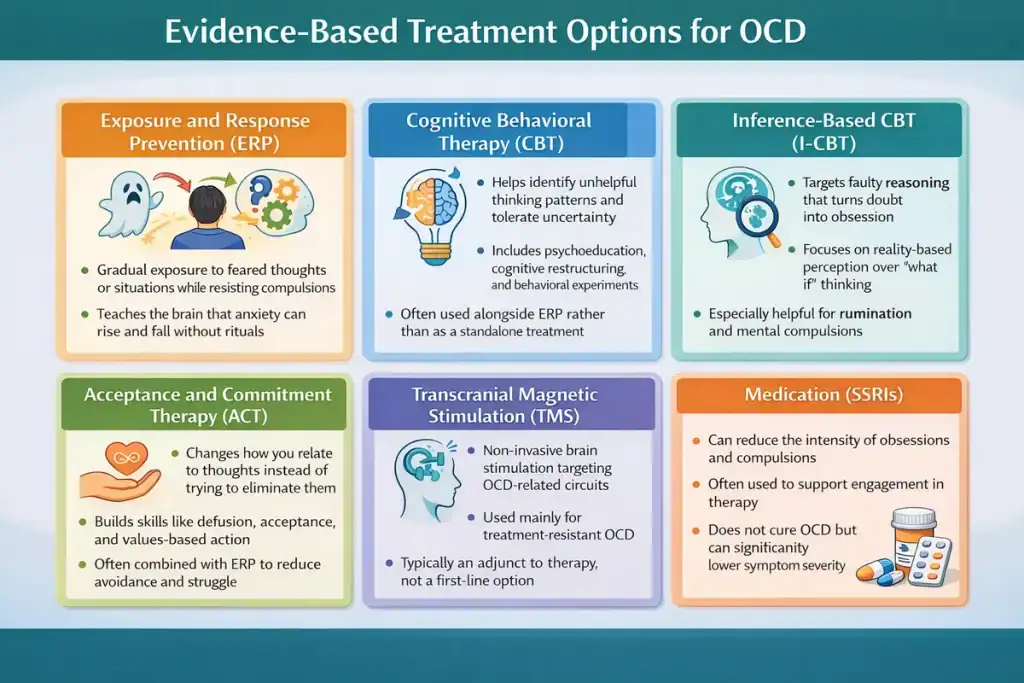

Evidence-Based Treatment Options

OCD is one of the most treatable mental health conditions when evidence-based approaches are used. Many people experience significant symptom reduction, improved functioning, and a better quality of life through therapy, medication, or a combination of both.

Recovery does not mean eliminating intrusive thoughts altogether; it means learning to respond differently to them. With the right support, skills, and treatment plan, people with OCD can return to school, work, relationships, and daily activities that once felt impossible.

Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP)

ERP is considered the gold-standard treatment for OCD and numerous clinical trials support its efficacy. ERP works by helping people gradually face feared thoughts, images, sensations, or situations (exposure) while resisting the urge to perform compulsions (response prevention).

Rather than trying to eliminate intrusive thoughts, ERP teaches the brain that anxiety can rise and fall on its own without rituals or avoidance. Over time, the brain learns that feared outcomes either do not happen or are more tolerable than expected.

ERP is typically done in a structured, collaborative way, with exposures tailored to the individual’s specific obsessions and compulsions. Although ERP can feel challenging at first, it is widely recognized as one of the most effective ways to reduce OCD symptoms and regain everyday functioning.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) helps people understand the relationship between thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. In the context of OCD, CBT focuses on identifying unhelpful thinking patterns, increasing tolerance for uncertainty, and reducing behaviors that maintain anxiety.

CBT may include psychoeducation about OCD, cognitive restructuring to examine how meaning is assigned to intrusive thoughts, and behavioral experiments that test feared assumptions. While traditional CBT alone is often less effective than ERP for OCD, many CBT skills are integrated into ERP-based treatment. These skills can help individuals recognize patterns, reduce mental rituals, and develop a more flexible response to distressing thoughts.

CBT provides a structured framework that supports insight, emotional regulation, and long-term coping skills when used appropriately for OCD.

Inference-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (I-CBT)

Inference-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (I-CBT) is a specialized form of CBT developed specifically for OCD. Rather than focusing primarily on anxiety reduction or exposure, I-CBT targets the reasoning process that leads people to doubt reality in the first place.

This approach helps individuals recognize how they move from neutral situations into obsessional doubt through faulty inferences, imagination, and “what if” reasoning. I-CBT emphasizes reconnecting with common sense, direct perception, and present-moment information instead of hypothetical possibilities.

It can be particularly helpful for people whose OCD is driven by intense doubt, rumination, or mental compulsions. Research suggests I-CBT may be an effective alternative or complement to ERP, especially for individuals who struggle with traditional exposure-based approaches.

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS)

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) is a non-invasive medical treatment that uses magnetic pulses to stimulate specific areas of the brain involved in OCD symptoms.

TMS does not require surgery or anesthesia and is typically administered in a clinical setting over several weeks. It is most often considered for individuals whose OCD has not responded adequately to therapy and medication alone.

Research suggests that targeting certain brain circuits may help reduce symptom severity in some people. TMS is usually used as an adjunct to therapy rather than a standalone treatment and is not appropriate for everyone.

While not a first-line intervention, TMS can be a valuable option for treatment-resistant OCD when delivered by trained medical professionals.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

ACT focuses on changing how people relate to their thoughts rather than trying to control or eliminate them.

In OCD treatment, ACT teaches skills such as cognitive defusion (creating distance from intrusive thoughts), acceptance of internal experiences, and commitment to values-based action. Instead of asking whether a thought is true or false, ACT encourages people to notice thoughts as mental events that do not require engagement.

This approach reduces struggle and helps individuals move toward meaningful activities even in the presence of anxiety or uncertainty. ACT aligns closely with modern OCD treatment principles and is often combined with ERP.

For many people, ACT offers a compassionate framework for reducing avoidance and rebuilding a fuller, values-driven life.

SSRIs

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly prescribed medications for OCD and are often used alongside therapy. SSRIs can help reduce the intensity and frequency of obsessions and compulsions, making it easier to engage in treatments like ERP or ACT.

Medication does not cure OCD, but it can lower symptom severity and emotional reactivity. SSRIs are typically prescribed by psychiatrists or primary care physicians, and effects may take several weeks to become noticeable.

Living With OCD: Skills and Coping Strategies

Here are practical, research-backed strategies that can help between therapy sessions or while seeking professional help.

Defusion Techniques (ACT)

Defusion is one of ACT’s six pillars, the others being self (perspective-taking), acceptance, presence, values, and action. Learning defusion means learning to see thoughts as thoughts, not truths or warnings.

Defusion is an incredibly valuable skill no matter who you are. Learning to leave judgment (of yourself or others) aside allows you to focus fully on the present, on what’s right in front of you. You can use several techniques to practice defusion. Here are a few:

- Labeling thoughts: Instead of treating a thought as a fact, gently label it as a mental event. Saying “My mind is telling me that I don’t love my partner enough” creates distance and reminds you that thoughts are experiences, not truths that require action.

- Repeating the thought in a silly voice: Silently repeat the intrusive thought using a cartoon voice, exaggerated accent, or playful tone. This helps weaken the emotional grip of the thought by highlighting that it is just language generated by the mind, not a serious message that must be obeyed.

- Imagining it floating by like a cloud: Picture the thought appearing in your awareness and then drifting past, like a cloud moving across the sky. You don’t need to push it away or analyze it. Just notice it come and go while you remain grounded in the present moment.

- Giving your mind a name and politely agree with it: Treat your mind like a slightly annoying guest who loves to complain. Give it a name (anything other than your own), and when it delivers judgment or criticism, respond internally with something like, “Thanks, Alex, I hear you.” This approach acknowledges the thought without engaging in debate or resistance.

Mindfulness Skills

Mindfulness is not just a buzzword or a passing fad. It has real, practical value for anyone who wants to relate differently to their thoughts, emotions, and experiences.

- Meditation: Meditation involves observing your inner experience (thoughts, emotions, sensations) without reacting to or analyzing it. Over time, this practice helps you notice intrusive thoughts more quickly and respond with less fear or urgency.

- Being deliberately present during certain tasks: Choose two or three everyday activities (e.g., brushing your teeth, washing dishes, walking) and commit to doing them with full attention. When your mind wanders, gently bring it back to what you are doing, strengthening your ability to stay grounded in the present moment.

- Reducing reassurance seeking: Not seeking reassurance is a central goal in OCD recovery and lies at the heart of Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP). While reassurance feels soothing in the short term, it reinforces the OCD cycle by teaching the brain that doubt is dangerous and must be eliminated.

Working on Values

Connecting with what truly matters helps guide actions when OCD tries to take over. Values function more like a roadmap than a goalpost: they are there to guide you, to point you in the right direction.

You can never “achieve” a value and this makes them fundamentally different from goals. Instead, values are something that you work on and strive to live by throughout your life. Though values may change with time, reflecting on them periodically and having them in mind is the best way to lead a meaningful life.

If you are looking to do some serious values work, check out Stephen C. Hayes’s A Liberated Mind. It introduces the reader to the concept and provides the framework needed to unearth your true values.

Delaying Compulsions

When you get the urge to perform a compulsion, pausing and trying to delay it, even if just for a few seconds at first, is an important step in the recovery process. Under the guidance of an ERP-trained therapist, you can develop a plan to tackle each fear and obsession by gradually delaying the associated compulsion for longer periods of time.

The goal is to stop compulsions altogether, but that often takes time. Even delaying a compulsion by a few seconds can weaken the OCD cycle. Importantly, delay is not meant to become a new rule or ritual, but a temporary tool to build tolerance for uncertainty and discomfort.

Developing Your Mental Flexibility

OCD is essentially mental rigidity made manifest. It is marked and sustained by rigid and intransigent thought patterns that leave little room for uncertainty, nuance, or ambiguity. Living with OCD can feel like wearing mental blinders that only allow you to see a narrow slice of reality, cutting you off from the full richness and complexity of life.

When someone with OCD encounters a thought, feeling, or sensation they don’t like or don’t understand, the mind tends to lock onto it immediately. It gets labeled as a problem that must be solved, analyzed, or eliminated. The assumption is clear: if something feels uncomfortable, it must be fixed. But what if it isn’t a problem at all? What if, instead of engaging in endless problem-solving, you allowed the experience to exist and approached it with curiosity?

This is where Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) becomes especially powerful. ACT is, in many ways, a therapy designed to cultivate mental flexibility. Rather than teaching you how to control your thoughts or feelings, it helps you change how you relate to them. The goal is to see the world, and your inner experience, through a wider lens: one grounded in openness, acceptance, and curiosity, rather than fear and avoidance.

Psychoeducation

Read, study, research. The more you know about OCD, the less likely you are to fall for the tricks your mind tries to play on you. Make it a habit: instead of mindlessly scrolling through YouTube or watching TV at night, spend some time reading psychology blogs or pick up a book on the subject.

Below, we share several excellent recommendations to help you better understand OCD and the therapies that can support recovery.

Supporting Someone With OCD

Supporting someone with OCD can be challenging, especially when their distress is real and immediate, and your instinct is to make it go away. The most helpful support starts with empathy, not problem-solving. Simple statements like “That sounds really hard,” “I believe you,” or “I know these thoughts don’t reflect who you are” communicate safety and understanding without feeding the disorder.

What’s less helpful (though often well-intentioned) are comments like “Just stop thinking about it,” “That doesn’t make sense,” or offering to check, reassure, or analyze the fear.

Reassurance may calm things briefly, but it strengthens compulsions and keeps OCD in control. Instead of reassuring, focus on validation. You can acknowledge the person’s distress without agreeing with the fear itself. Validation sounds like recognizing how painful the anxiety is, not confirming what OCD is saying.

Encouraging treatment is also an act of care. Gently suggest evidence-based options like ERP, ACT, or I-CBT, and support them in staying consistent with therapy. Most importantly, avoid participating in compulsions. Setting kind, clear boundaries helps protect both of you and supports real recovery.

A Real-Life Example: Supporting a Partner With OCD

In A Liberated Mind, Dr Hayes goes over a formula for supporting people with hard, OCD-driven thoughts by helping them develop their mental flexibility.

Instigate, Model, and Reinforce it, From, Toward and With It!

What this means is that you:

- Instigate: You gently prompt flexibility by inviting a different way of relating to thoughts (e.g., curiosity, openness, or noticing rather than fixing).

- Model: You demonstrate psychological flexibility yourself by responding to difficult thoughts calmly, openly, and without urgency or control.

- Reinforce: You acknowledge and support any movement toward flexibility, however small, rather than focusing on symptom reduction or certainty.

- From flexibility: You operate from your own stance of acceptance and openness, rather than fear, urgency, or the need to correct.

- Toward flexibility: Your aim is to help the other person build their own capacity to tolerate uncertainty and relate differently to thoughts.

- With flexibility: You adapt moment by moment, staying responsive and compassionate instead of rigidly applying rules or techniques.

Here is a real-life example of this formula at work:

Daniel has relationship-focused OCD. He’s been stuck all morning on the thought “What if I don’t really love you and I’m lying to both of us?” His anxiety is high, and he’s clearly looking for reassurance. His girlfriend, Maya, has learned about OCD and ACT-based support.

Daniel: “I keep thinking I don’t love you enough. If I really loved you, I wouldn’t be having these thoughts. What if this means we shouldn’t be together?”

Instead of arguing with the thought or reassuring him, Maya gently shifts the frame.

Maya: “That sounds really painful. Can we pause for a second and notice what your mind is doing right now, instead of trying to answer it?”

She’s not trying to solve the doubt. She’s inviting a different relationship to it (instigating)

Maya stays calm and open, showing that uncertainty doesn’t need to be treated as an emergency (modelling).

Maya: “I’m okay sitting here with you while this thought is here, even if we don’t figure it out right now.”

She models acceptance rather than urgency.

When Daniel hesitates and doesn’t immediately ask for reassurance, Maya notices and supports that (reinforcing flexibility).

“I really appreciate you not chasing the answer just now. I know that’s hard.”

She reinforces the process, not the outcome.

Maya reminds herself that Daniel’s doubts are OCD-driven, not a verdict on the relationship. She doesn’t take the content personally or try to defend herself (from flexibility).

Her goal isn’t to convince Daniel that he loves her. It’s to help him tolerate the doubt without compulsions (towards flexibility).

Maya: “You don’t have to prove anything to me right now. Let’s just let the feeling be here and keep living our day.”

When Daniel circles back to the thought later, Maya doesn’t snap or rigidly apply a rule (with flexibility).

“I hear the doubt coming back. We can notice it again, or we can shift our attention,your call.”

She stays responsive, not rigid.

When to Seek Help: Red Flags That It’s Time

When OCD symptoms start interfering with daily routines, such as work, sleep, or basic self-care, it may be time to seek additional support. Reaching out for professional help is not a failure: it’s a meaningful step toward relief and recovery.

Here are some signs you should be working with a therapist:

- Compulsions interfere with daily routines.

- You start avoiding situations, tasks, or people, which severely limits your world.

- Relationships feel strained, especially as reassurance-seeking, withdrawal, or emotional exhaustion take a toll.

- Rumination lasts hours, leaving you mentally drained and stuck in the same loops.

- Compulsions feel impossible to resist.

- Shame or distress around your thoughts is increasing.

How to Find a Therapist

Finding the right therapist is an important step in recovering from OCD. Not all mental health professionals are trained to treat OCD effectively, so it’s worth being selective.

Look for clinicians who explicitly list experience with evidence-based treatments such as Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), or Inference-Based CBT (I-CBT).

If local options are limited, teletherapy can be just as effective and far more accessible. Platforms such as NOCD, OCD Anxiety Centers, and other ERP-focused telehealth clinics offer remote treatment with clinicians trained specifically in OCD.

Helpful therapist directories include:

- International OCD Foundation (IOCDF): This organization offers a global directory of OCD-trained clinicians.

- OCD Action: Visit the website of the UK’s largest OCD charity to find therapist listings and support resources.

- NOCD: NOCD specializes in the treatment of OCD and has a directory of OCD-specialized providers.

- OCD Anxiety Centers: With in-person and virtual programs that are centered on ERP, OCD Anxiety Centers may have a program that’s right for you.

Before starting, don’t hesitate to ask potential therapists about their experience treating OCD and the methods they use. If you’d like a first-hand account of what the process of finding a therapist can be like, check out this post about my OCD recovery story.

What to Expect in the First Sessions

In the first sessions, your therapist will focus on getting a clear picture of your symptoms, history, and how OCD shows up in your daily life. This assessment helps determine the most appropriate treatment approach and ensures nothing important is overlooked.

You’ll also receive clear, practical education about OCD: how intrusive thoughts and compulsions work, why they persist, and what actually helps reduce them. Understanding the OCD cycle is often a relief in itself.

Together, you and your therapist will set collaborative, realistic goals for treatment, based on what matters most to you. From there, you’ll begin developing a plan for exposures and skill-building, moving at a pace that is challenging but manageable.

Resources

Helpful Tools and Organizations

Recommended Books:

- The Happiness Trap by Russ Harris and Steven C. Hayes

- Getting Over OCD by Jonathan S. Abramowitz

- Overcoming OCD by David Veale and Rob Willson

- A Liberated Mind by Steven C. Hayes

- Freedom from Obsessive Compulsive Disorder by Jonathan Grayson

- The Mindfulness Workbook for OCD by Jon Hershfield, Tom Corboy MFT, and James Claiborn

OCD FAQ

OCD symptoms may come and go, but the disorder rarely resolves on its own. Long-term improvement typically requires evidence-based treatment, such as ERP, ACT, or I-CBT, which address the underlying OCD cycle rather than just reducing anxiety temporarily.

Online therapy improves access to OCD-trained clinicians, reduces barriers like location and waitlists, and offers structured, ongoing support through video sessions, exercises, and between-session guidance. For many people, this flexibility makes it easier to stay consistent with treatment and apply skills in daily life.

Some of the best apps to manage your OCD symptoms and increase mindfulness include MoodTools and Clarity. Both are based on the principles of CBT, which means they help you unveil distorted thinking patterns.

Visit the websites of the International OCD Foundation and NOCD to find learning resources related to OCD. Additionally, you can learn Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) at ACT Courses, which offers training for therapists as well as the general public. There are also many apps to practice ACT and CBT, such as ACT companion and MindDoc.