Key Takeaways

- Relationship OCD (ROCD) is a subtype of OCD that centers on intrusive doubts and anxiety about relationships.

- ROCD fears are usually ego-dystonic: people feel tormented by their doubts precisely because they deeply care about love, commitment, and being a good partner.

- ROCD can focus on the relationship itself (relationship-centered) or on the partner’s traits (partner-focused), and many people experience a mix of both.

- The problem is not that the person has doubts. The problem is that their thinking follows the OCD cycle based on anxiety and compulsions.

- Effective treatment usually involves ERP, ACT, and CBT, which help people face uncertainty, reduce compulsions, and base relationship decisions on values rather than anxiety.

- Partners can support loved ones with ROCD by offering empathy instead of reassurance and setting healthy boundaries.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes, not medical advice.

Relationship OCD: How Anxiety Can Disrupt Healthy Relationships

Emily has been with her partner for three years. One evening, while they are cooking dinner together, a sudden thought hits her:

“What if I don’t love him enough?”

The question feels sharp, urgent, and strangely important. She tries to shrug it off, but the doubt lingers. The next morning, as they drink coffee together, another intrusive thought appears:

“Shouldn’t I feel more excitement? What if this means the relationship is wrong?”

Emily loves her partner deeply. They laugh together, share the same values, communicate well, and have built a stable, caring life side by side. Nothing in the relationship has changed, but something in her mind has. The more she analyzes her feelings and thoughts, the more confused and anxious she becomes.

She feels the need to be certain that she is still in love with him. Otherwise, it wouldn’t be fair to him, she thinks. The problem is that the more she struggles to convince herself of her love, the more uncertain it all becomes.

She begins mentally reviewing memories (“I did feel in love last month, right?”), comparing her relationship to others, googling signs of compatibility, and silently checking whether a “spark” is present.

Emily is experiencing Relationship OCD (ROCD).

What Is Relationship OCD?

Relationship OCD (ROCD) is a subtype of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in which intrusive thoughts and doubts interfere with a person’s ability to experience healthy, fulfilling relationships. These intrusive thoughts generate anxiety and discomfort that significantly affect the person’s quality of life.

People with OCD often feel that certain important areas of their lives are “not quite right” and become fixated on trying to resolve that feeling. In ROCD, this sense of uncertainty becomes centered on relationships.

It is important to understand that ROCD does not mean the relationship is unhealthy. The problem lies in the OCD cycle. In fact, people with ROCD often have caring, stable relationships.

ROCD does not mean the relationship is unhealthy. The problem lies in the OCD cycle

ROCD fears and obsessions are typically ego-dystonic, meaning they go against the person’s values. Someone who obsesses about their relationship does so precisely because relationships matter deeply to them.

People with ROCD often place great importance on romantic relationships; as a result, even minor negative events can feel overwhelming and trigger intense self-doubt.

In some cases, ROCD is fueled by extreme or rigid beliefs about relationships. For example, a person might believe that a relationship must feel “perfect” at all times to be valid, or that any moment of doubt means the relationship is toxic or doomed. These unrealistic expectations make ordinary relationship fluctuations feel threatening.

Quick Facts About Relationship OCD

- It is a subtype of OCD.

- ROCD is not a separate, diagnosable mental disorder; it is an expression of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder.

- There are two broad forms: relationship-centered ROCD and partner-focused ROCD.

- ROCD is not limited to romantic relationships; it can also appear in parent–child relationships or even in a person’s relationship with God.

- Research shows that ROCD can be just as disabling as other forms of OCD.

- ROCD often appears in early adulthood as the person starts dating.

- It affects men and women equally.

- Research shows that ROCD symptoms are not linked to the length of the relationship or to biological sex or gender.

What Relationship OCD Is Not

Relationship OCD is not evidence that you are in the wrong relationship, nor is it a sign that you do not love your partner or that you are fundamentally incompatible. It does not mean you lack commitment. Finally, it is not intuition: ROCD often disguises itself as a “gut feeling,” even though the distress comes from anxiety, not truth.

Relationship OCD or Normal Anxiety?

It is perfectly normal to feel unsure about a partner from time to time; that is part of dating and getting to know someone. Normal relationship anxiety is flexible: the person can hold doubt lightly, explore it over time, and stay open to learning whether the relationship is right for them.

Relationship OCD, however, is marked by rigidity and urgency. Doubts feel threatening, intolerable, and in need of immediate resolution. This leads to compulsions such as seeking validation, mentally checking feelings, or analyzing every interaction. The problem is not the doubt itself but the obsessive need for certainty.

This YouTube video does a great job at explaining the difference between ROCD and regular relationship anxiety and provides valuable examples of each.

| Relationship OCD (ROCD) | Normal Relationship Doubt |

|---|---|

| Doubts feel urgent, threatening, and unacceptable | Doubts feel uncomfortable but manageable |

| Strong need for immediate certainty or answers | Willingness to give things time and let clarity develop naturally |

| Triggers compulsions | Does not lead to repetitive checking or compulsive behaviors |

| Thoughts become rigid, repetitive, and intrusive | Thoughts are flexible and come and go without dominating the mind |

| Doubts contradict the person’s genuine values and desires (ego-dystonic) | Doubts arise from natural uncertainty |

Types of Relationship OCD

Generally speaking, ROCD can be categorized into two main presentations:

- Relationship-centered ROCD.

- Partner-focused ROCD.

Both forms can appear together, and people often move between the two.

Relationship-Centered ROCD

In relationship-centered ROCD, the person’s fears and worries revolve around the state of the relationship itself. They may obsessively question:

- whether the relationship is “right”.

- whether they truly love their partner.

- whether their partner truly loves them.

- whether they are making a mistake by staying.

These doubts are intrusive, persistent, and ego-dystonic, meaning they go against the person’s genuine values and feelings.

Partner-Focused ROCD

In partner-focused ROCD, intrusive thoughts and compulsions center on the partner’s qualities. People may obsess about their partner’s:

- physical appearance.

- personality traits.

- habits and preferences.

- perceived flaws or imperfections.

These intrusive thoughts are often not a reflection of genuine dissatisfaction; they are driven by intolerance of uncertainty and the OCD cycle.

People with partner-focused ROCD may also fixate on their partner’s past relationships. For example, they might worry that their partner had better sex with an ex, or draw distorted conclusions about their partner’s character based on who they dated previously. These thoughts are common in ROCD and stem from the same anxiety-driven need for certainty and reassurance.

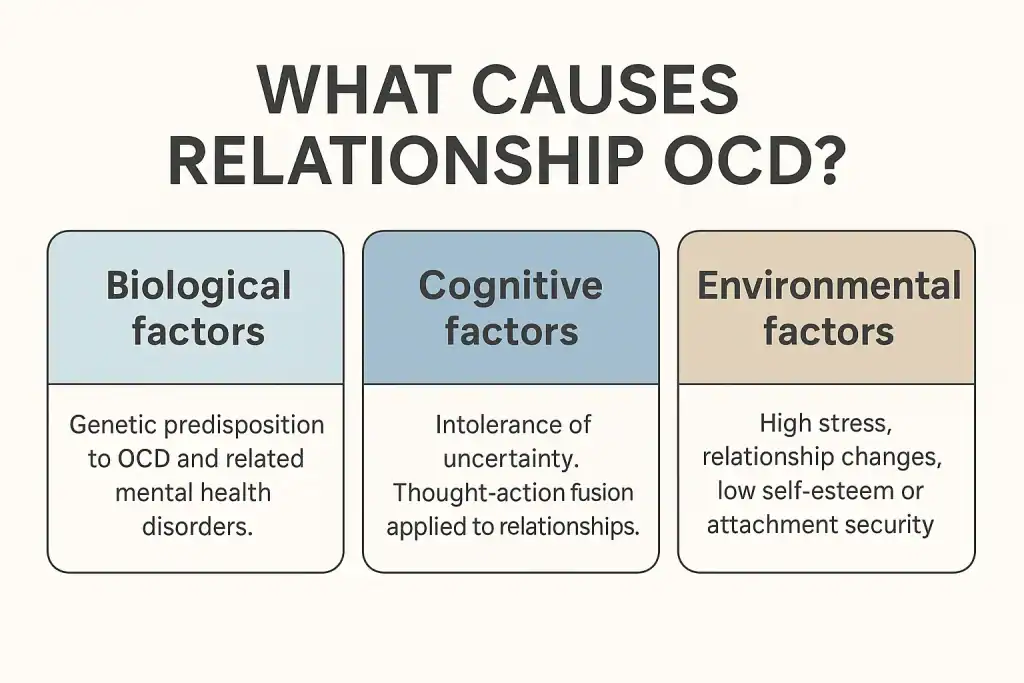

What Causes Relationship OCD?

Relationship OCD does not occur in isolation. It is an expression of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder, not a separate mental disorder. People who experience ROCD typically have other OCD symptoms, either in the present or earlier in life.

Like all forms of OCD, ROCD is believed to arise from a combination of biological, psychological, and environmental factors. Research suggests that OCD has a genetic component that increases a person’s vulnerability. Depending on life experiences and stressors, this predisposition may remain dormant or may be triggered by certain events.

It is also common for ROCD to emerge during times of heightened emotional significance, such as entering a new relationship, committing to a partner, or experiencing changes in attachment, stress, or self-esteem. These moments can activate the brain’s threat-detection and uncertainty systems, making intrusive thoughts about relationships feel especially distressing.

Other factors that contribute to ROCD are difficulty dealing with uncertainty, overidentifying with your thoughts (thought-action fusion), and an inflated sense of responsibility (e.g., “Am I leading him or her on if I have doubts and do not share them immediately?”).

Examples of Relationship OCD

Case 1: Fear of Not Being Attracted Anymore (Partner-Focused ROCD)

Mark has a long history of OCD. After watching a video about “signs you’re falling out of love,” Mark began doubting his feelings for his partner. Since then, he has been tormented by thoughts like, “What if I’m not attracted to her anymore?” or “What if I’m lying to her and she deserves better?”

At times, the intrusive thoughts go even further, telling him she isn’t beautiful or that he should feel something he doesn’t.

Hoping for clarity, Mark reads story after story about ROCD online and analyzes his own thoughts and feelings for hours each day. At first, these compulsions gave him temporary relief, but now they only make him feel more confused.

Mark has even begun questioning whether he actually has ROCD or whether he is simply “using OCD as an excuse” to avoid admitting the relationship is over (a common theme among ROCD sufferers).

Before these intrusive doubts appeared, Mark used to feel excited to see his partner. Now he feels mostly anxious and stressed, interpreting the anxiety itself as “proof” that he has fallen out of love. The obsessive doubts have begun spilling into other areas of his life, including work, leaving him exhausted and overwhelmed.

Case 2: Fixation on Partner’s Physical Flaws (Partner-Focused ROCD)

John has been with his partner for over two years. Recently, the thought struck him that something is not quite right with the face of his partner. He can’t stop thinking that her face isn’t the “right” shape: “this is not the shape of an attractive face,” he thinks.

John has been having these thoughts for months now. It’s the first thing that pops into his mind when they sit together at the kitchen table for their morning coffee. Similar thoughts follow him throughout the day, leaving him anxious and distracted.

John loves his partner. They get along well and share similar values, and he does find her beautiful and attractive. His fixation with the shape of her face does not reflect actual preference or reality. And yet, the intrusive thought that her face isn’t “right” keeps haunting him, undermining his enjoyment of the relationship.

Case 3: Fear of Not Being Desired (Relationship-Centered ROCD)

Emma is consumed by fears about her boyfriend’s feelings toward her. She constantly worries that he finds other women more attractive, that he is losing interest, or that he might cheat. Everyday moments (a glance, a pause, a shift in tone) become potential “signs” that something is wrong.

These fears lead her to become hypervigilant about her boyfriend’s behavior. She watches how he looks at people around them, checks his social media activity, and compares herself to other women to see if she “measures up.”

She also engages in compulsive behaviors meant to reassure herself, such as trying to make herself more desirable or repeatedly analyzing his reactions to her.

Emma’s past experiences with trauma complicate her fears, making the intrusive thoughts feel even more convincing. Although she wonders whether her symptoms are trauma-related, OCD-related, or both, the result is the same: she feels overwhelmed, insecure, and unable to trust her own interpretations of the relationship.

Despite being in a caring partnership, Emma finds herself stuck in a cycle of doubt and fear. She longs to feel at ease with her boyfriend again but is unsure how to break free from the intrusive thoughts that make everything feel uncertain.

Case 4: Fear of Losing Feelings (Relationship-Centered ROCD)

Sofia had been in a happy relationship for several months. The first part of their relationship felt effortless: full of affection, excitement, and long conversations. She felt deeply connected to her partner and even imagined a future together.

After recovering from a period of illness and stress, Sofia noticed a sudden shift. Almost overnight, she felt disconnected and numb. The urge to cuddle, kiss, or seek closeness wasn’t as strong. She found herself wanting more time alone and interpreted this change as “proof” that she was falling out of love.

These doubts quickly spiraled. She began asking herself:

- “Why don’t I feel the same as before?”

- “What if this means my feelings were never real?”

- “Am I lying to him by staying?”

- “What if I’m not meant for love at all?”

Whenever she remembered their good moments, she felt relief. But as soon as they met in person, her anxiety returned, convincing her that her lack of butterflies meant something was deeply wrong. She became terrified that she would never regain the feelings she once had.

Although Sofia’s partner remained loving and supportive, she was weighed down by guilt and confusion. She feared hurting him and doubted every emotion she did or did not feel. The intrusive thoughts began dominating her day, leaving her exhausted and unsure of what was real and what was anxiety.

Sofia’s experience is a classic example of relationship-centered ROCD: intrusive doubts misinterpreted as signs of falling out of love, emotional checking, and a desperate attempt to “feel the right feeling again.”

Signs and Symptoms of Relationship OCD

There are common patterns of intrusive thoughts that we see in people with ROCD.

These thinking patterns may look different on the surface, but underneath them lies the same mechanism: an intolerance of uncertainty combined with compulsive attempts to gain clarity, certainty, or reassurance. Recognizing the patterns is a powerful first step in loosening their grip.

Focusing on Your Partner’s Perceived Flaws

- “What if someone better is out there?”

- “My partner isn’t attractive enough because of this flaw.”

- “What if this small imperfection means we’re incompatible?”

Focusing on Your Own Perceived Flaws

- “Am I a good enough partner for them?”

- “What if they realize they could do better?”

- “What if I’m not lovable?”

Questioning Your Feelings Toward Your Partner

- “Do I really love my partner?”

- “Why don’t I feel as attracted as before?”

- “What if I’m making a mistake staying together?”

- “Am I lying to them if I’m not 100% sure about the relationship?”

Comparing Your Relationship to Others

- “Are my friends happier than I am in their relationships?”

- “Other couples seem more romantic; what’s wrong with us?”

Anxiety About Unwanted Impulses or Thoughts

- “What if I secretly want to cheat?”

- “What if having the thought of leaving him means I actually want out?”

Fear About the Stability of the Relationship

- “What if my partner cheats on me and I don’t see it coming?”

- “What if we break up in the future?”

Common Relationship OCD Compulsions

- Rumination: The person spends hours analyzing their thoughts, feelings, and past interactions in an attempt to gain clarity. Unfortunately, the more they think, the more confused and distressed they become.

- Repeatedly checking feelings: People with ROCD often scan their emotions to see whether they feel “in love” at that exact moment (“Do I feel enough love right now?”).

- Physical checking (testing attraction): A person might stare at their partner’s face or body, mentally evaluating their level of attraction.

- Avoidance behaviors: Some individuals avoid situations that trigger doubtful thoughts, such as intimate moments, difficult conversations, or spending time together.

- Comparing partner to ex-partners or strangers: The person may constantly assess whether their current partner “measures up” to previous partners or strangers. They might also compare their relationship to friends’ relationships or idealized versions in movies.

- Excessive reassurance seeking: People may ask friends or family to validate their relationship or confirm that their partner is “right for them.” They might also ask their partner whether they are lovable enough, attractive enough, or committed enough.

- Googling signs of compatibility: Searching online for quizzes, articles, or “signs you’re in the right relationship” becomes a repetitive strategy to reduce anxiety.

- Mentally reviewing past memories: People might replay old moments in their relationship to “check” whether they felt more love or attraction in the past.

- Thought neutralization: When a distressing thought appears, the person may try to replace it with a more positive one or mentally “cancel it out.”

- Testing feelings: Some individuals experiment with kissing, touching, or imagining scenarios to see if they feel a “spark.” Because emotions can’t be forced on command, this test almost always backfires.

- Attempting to change the partner: People may try to correct their partner’s behavior or physical appearance to fit an idealized image.

- Confession compulsions: Feeling the urge to confess intrusive doubts, thoughts, or feelings to your partner to relieve guilt or anxiety. This often temporarily reduces anxiety but damages the relationship and strengthens the cycle.

The OCD Cycle in ROCD

ROCD follows a predictable cycle: a trigger leads to an intrusive thought, which sparks anxiety and pushes the person into compulsions. These compulsions bring brief relief, but ultimately reinforce the obsession and create more doubt. Each reassurance attempt makes the fear feel more real, trapping the person in the cycle.

How to Overcome Relationship OCD

Treatment for ROCD seeks to reduce obsessive thoughts and compulsions. The goal is to minimize these OCD-related symptoms so that the person can fully experience their relationship. Once that’s achieved, the person can make a decision about the relationship based on their actual experience, not on OCD-motivated fears.

As far as recommended treatment, it is no different from other OCD types.

ERP (Exposure and Response Prevention)

ERP helps people with ROCD face relationship triggers while resisting compulsions. Exposures may include looking at a partner’s photo without analyzing attraction, writing uncertainty scripts, or allowing doubt to be present. Response prevention means not seeking reassurance and letting intrusive thoughts rise and fall on their own.

ACT (Acceptance and Commitment Therapy)

ACT teaches you to separate yourself from intrusive thoughts through defusion exercises that reduce their power. Instead of trying to “fix” doubt, you learn to let thoughts come and go while choosing values-based actions — showing care, presence, and commitment even when fear or uncertainty shows up.

CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy)

CBT can help identify and challenge unhelpful relationship myths, such as “true love should always feel certain,” and address perfectionistic beliefs about what a relationship “should” look like. While not a standalone treatment for ROCD, CBT can complement ERP and ACT by reshaping rigid thinking patterns.

Daily Practices That Support Recovery

While therapy is the foundation of ROCD recovery, daily habits play a powerful role in calming the mind and reducing compulsions. These simple routines help you stay grounded, strengthen emotional resilience, and support long-term progress.

- Mindfulness: Helps you notice intrusive thoughts without reacting to them or getting pulled into analysis. Meditation is a great way to work on your mindfulness.

- Keeping a journal: Keeping a diary helps you keep track of patterns, triggers, and compulsions, making them easier to address in therapy.

- Reconnecting with values: Taking the time to examine your values and striving to live in alignment with them will help you live more meaningfully.

- Sleeping, eating well, and exercising: Having a healthy daily routine supports emotional stability and reduces vulnerability to intrusive thoughts.

- Communicating with your partner: Talk openly about the challenges you face, but avoid turning the conversation into reassurance-seeking. This strengthens connection without reinforcing OCD.

The Effect of OCD on Partners

ROCD can create significant strain within a relationship, affecting not only the person with OCD but their partner as well. When intrusive thoughts are shared openly, the partner may take them personally or misinterpret them as meaningful, sometimes even beginning to doubt the relationship themselves. Being pulled into constant reassurance can also feel exhausting, leaving partners emotionally depleted and unsure how to help.

Despite this, partners can support their loved one in a healthy way, without becoming part of the OCD cycle. The most supportive stance is to offer empathy rather than reassurance: acknowledge their distress, validate their feelings, and gently redirect them toward therapeutic tools such as ERP skills or planned exposures. Setting boundaries around reassurance (“I care about you, but I can’t give reassurance, that’s OCD talking”) is essential to stopping the cycle rather than feeding it.

At the same time, partners must protect their own emotional well-being. This means recognizing that ROCD-related doubts reflect anxiety, not the true quality of the relationship. Partners should create space for their own feelings, maintain supportive friendships, and seek guidance from a therapist if needed.

Establishing healthy communication patterns, practicing self-care, and refusing to take OCD-driven statements personally allows partners to stay grounded and supportive without sacrificing their own mental health.

The Gordian Knot of ROCD

ROCD, like Harm OCD and all other OCD subtypes, brings to mind the Greek parable of the Gordian knot.

According to the legend, King Gordias tied an impossibly tangled knot. A prophecy declared that whoever could untie it would go on to rule Asia. Many tried to solve it the “proper” way: pulling at its loops, analyzing its structure, trying to work out a logical method. None succeeded. The knot was too tight and too complex.

Then came Alexander the Great.

Instead of trying to “solve” the knot the traditional way, he simply cut through it with his sword.

He stopped playing by the knot’s rules.

Alexander did not “engage” with the knot as the others did. He did not try to unravel the knot logically by pulling its threads. Instead, he sought out a more creative (if drastic) solution.

Like Alexander, we must learn to not engage with our obsessive thoughts from a logical standpoint by pulling at the “threads” (analyzing, checking, ruminating).

Recovery requires a different approach: you must “cut through the knot” by refusing to engage in compulsions, even when the urge feels overwhelming.

What ROCD Teaches Us About Love and Uncertainty

- Love is an action, not a feeling.

- Uncertainty is universal.

- Obsessions distort the meaning of normal fluctuations.

- ROCD sufferers often become deeply self-aware and resilient.

ROCD Resources: Books, Podcasts, and Communities

- Relationship OCD: A CBT-Based Guide to Move Beyond Obsessive Doubt, Anxiety, and Fear of Commitment in Romantic Relationships by Sheva Rajaee (book)

- Thriving in Relationships When You Have OCD: How to Keep Obsessions and Compulsions from Sabotaging Love, Friendship, and Family Connections by Amy Mariaskin (book)

- Overcoming ROCD: Practical, self-help exercises to unshackle from the chains of Relationship-focused Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (Overcoming OCD) by Dr. Sunil Punjabi (book)

- The OCD Stories (podcast)

- r/ROCD subreddit (community)

- ACT for the Public (email list)

Relationship OCD FAQ

There are several helpful communities for people with ROCD. The OCD subreddit and ROCD-specific subreddits offer peer support and shared experiences. “ACT for the Public” (email group) and “The OCD Stories” community provide high-quality discussions grounded in evidence-based treatments. Many countries also have local OCD foundations with support groups, both online and in person.

A clear way to explain ROCD is to emphasize that the intrusive doubts come from anxiety, not from the quality of the relationship or your true feelings. You can say something like: “These thoughts feel real, but they are actually part of OCD, not a reflection of how I feel about you.” It also helps to share resources, describe compulsions to avoid reassurance patterns, and invite them to learn about the OCD cycle with you.

Yes. Several online therapy platforms specialize in OCD treatment, including ROCD. NOCD is the most well-known, offering licensed therapists trained in ERP and ACT. Other platforms like OCD Specialists, OCD Anxiety Centers, and various telehealth CBT/ERP clinics also treat ROCD specifically. Always confirm that the therapist is ERP-trained and familiar with ROCD.

No. Although ROCD most often appears in romantic relationships, it can occur in any relationship that feels emotionally significant. People may experience ROCD toward a parent, child, close friend, or even their relationship with God or spirituality. The pattern (intrusive doubts followed by compulsions) remains the same, regardless of the relationship.